Manga vs Comics: How the Base Influences the Superstructure

Manga vs Comics: How the Base Influences the Superstructure

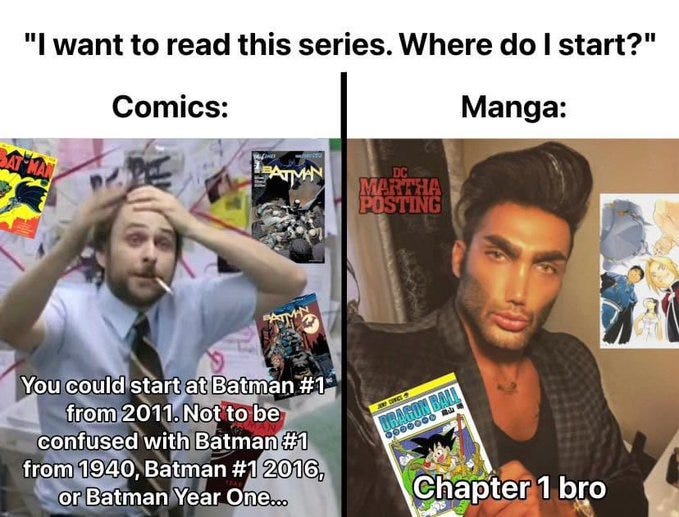

This is actually a great example of how material concerns influence culture. The differences (including this one) between manga & american comics don’t come from “japanese culture” or whatever, but from the economics of selling anthology magazines vs individual books.

In American comics, stuff runs as individual comic books and then may eventually get collected into trades, if the individual books sell well enough. The books themselves are treated as totally disposable except by would-be collectors. Back-issues are available from the printer for a very short time, and series go on for a long time. Comic readers can’t expect to order the whole run of something, and comic writers therefore need to create comics that encourage but do not depend upon familiarity with previous issues. With this model, it’s easier to turn some profit but it’s harder to get really big: you need a superstar title.

The superstar title will fund the other titles but it won’t drive sales for them particularly, and that’s sort of why we have Marvel and DC and then a million tiny players, and then within DC you have Batman and Superman and a million tiny players. (Marvel sales are driven by the movies now instead of the other way around and they always had a lot of focus on big sprawling interlocking stories involving bit players, but still, circa 1995, it was X Men and Spiderman and a million niche titles.)

At the same time that the disposability of individual books drives story structure, it’s also integral to the collector market. For a long time, comic sales were driven in part by appealing to novice collectors’ idea of what would be worth a lot of money in the future — basically, a combination of rarity and notability, which, in the handful of genuine cases where comics are worth a lot of money, was driven by disposability: most of the people who had copies of Action Comics #1 threw them out after reading them, and so the handful of well-preserved copies became very expensive once Superman became an important franchise. We got a bunch of reboots, large scale events, and limited/special edition comics in the 90s in order to appeal to naive collectors who thought that these were indicators of investment potential. Not reprinting old books is an important part of catering to these collectors (although it was clear to many people, even at the time, that comic collectors were being gamed by DC and Marvel with false signals and that none of these comics would actually become good investment material).

Japan does things a little differently, not due to some deep and abiding cultural difference but because of conditions on the ground in the early 20th century. Manga comes in weekly manga magazines, which contain a ton of different series all mashed together. Odds are you’ll follow more than one series in the magazine, if only to justify the purchase. If you don’t — well, tankoban releases (the equivalent of trades) will generally cover the entire run. One result: you probably keep these heftier issues around longer. The big manga magazines are weekly and have 30 page chapters. You’re expected to have access to the whole story (maybe with a delay), whereas with american comics, you will never see a Superman #1 or a full reprint of it — you have to rely on summaries. (You still have summaries in manga, but… well, to be as big and long as Batman you need to be as popular as Batman, and that’s really just One Piece. The rest of the manga ecosystem is more like indie comix: lots of stories run to completion.)

By having anthology magazines, the sales of one series supports others in a way where it’s difficult to reliably figure out which series is the superstar. All the minor series in a magazine sell each other. So on the one hand, the size of the package changes how disposable each issue is seen to be, and that changes how much of a coherent serial story you’re telling. On the other hand, packaging different stories together makes the popularity landscape a little flatter.

Both american comics and manga often tell serial stories (though gag manga and 4koma, which are more episodic and are a little more like newspaper comics with higher production values, are very popular). However, the granularity and tempo of these stories is affected, in a non-linear way, by the economics of their publishing industries (which are influenced by the distribution formats).

A superstar comic series, once established, is extremely valuable — and extremely hard to replicate — so once Batman or Superman starts, you never bring that story to an end. Batman has his own books and Batman books don’t come packaged with other stories about other characters (except during cross-over events); if you want to see Batman and Superman together, you’re expected to buy not just a Batman book and a Superman book but also a Justice League book. Rather than any story coming to an end (and therefore taking the name & some readers’ standing orders temporarily out of use), reboots and big retcon events will reset the stories while avoiding interrupting the incoming flow of money. Despite massive changes, popular characters in the big two’s stable of comic characters run continuously under the same branding for decades. At the same time, these characters are rarely creator-owned — in part because creator-owned characters are creator-controlled characters (so at best there will be some difficulty in making them survive longer than their creators).

This is very different from manga, which because of packaging, has an easier on-ramp: extremely successful franchises are often extended beyond the point of remaining enjoyable, but they die or are replaced all the time, and new franchises are spawned constantly because of the need for content to fill out the rest of the magazine — and characters and stories will generally stick with the same authors and artist for longer, simply because when the deals are initially made, all these franchises are of unknown value. Keeping a variety of genres in a popular manga magazine keeps the readership wide, and sometimes spawns unexpected hits. For instance, the biggest manga magazine, Shonen Jump, is heavily associated with fantasy-martial-arts titles with teenage boy protagonists, but it has hosted romance-comedy, horror, sports, and industry metacommentary series that have gone on to become huge franchises — most of which have since ended. With the exception of One Piece, all the top 10 most popular series in Shonen Jump from 10 years ago have already ended, while some of the low-ranking series have been running for decades.

For a comic series to go on forever, it has to give up on the idea that the average reader has read the beginning of the series, even if on an issue-to-issue basis there may be an intense dependence on continuity. Both manga and american comics will often break runs into arcs — runs of issues where there’s a lot of internal issue-to-issue continuity, but where the beginning and end is an easy jumping-on point. However, the more manageable it is to read the entire series, the more reasonable it is to make any current event depend upon familiarity with a detail of a much earlier event — in other words, short series can be extremely cohesive, while long series can’t without alienating readers.

Seemingly simple and apolitical decisions like “should we package different series together” have enormous knock-on effects on genre.